Chris Blackwell’s Jamaican Retreat

The Island Records founder and hotelier shares his love for Jamaica through his latest homegrown hit—his farm.

ONE LOVE | The stone farmhouse at Pantrepant, one of Blackwell’s favorite retreats. ‘I fell in love with the tree,’ he says. ‘So I bought the tree as well as everything that came with it.’

NEARLY A QUARTER CENTURY AGO, when Chris Blackwell bought Pantrepant—a 2,500-acre cattle farm in Jamaica’s Cockpit Country, 29 miles inland from Montego Bay—his entrepreneurial dreams lay elsewhere.

In 1989, the record producer had sold his wildly influential label Island Records to Polygram for $300 million and was establishing a new hotel venture in Miami. Pantrepant would serve as a home and private retreat, a place where he could unwind with friends such as Bono, Grace Jones and Bob Marley’s family. He loved its towering guango tree, the majesty of the white Brahman cattle, the fruit trees filled with birds. What he didn’t know was that more than two decades later the farm would, like reggae, become another vehicle for showcasing Jamaica to the world.

This summer, Pantrepant will launch regular farm-to-table dinners for guests of Blackwell’s three luxury resorts: Goldeneye, situated on the country’s northeast coast, as well as its sister Island Outpost properties—Strawberry Hill near Kingston and The Caves in Negril. Guests will have the opportunity to visit the farm and pick their own callaloo and milk a cow. Blackwell has never liked the limelight and always kept Pantrepant private, so the news came as a surprise. At Goldeneye, he explains that the move is, like most things he does, a slow and organic outcome of his passions. He also reveals an ulterior motive:

I’m intent on marketing Jamaica,

– he says.

Jamaica has the best coffee, the best sugar, the best ginger and some of the best cocoa in the world.

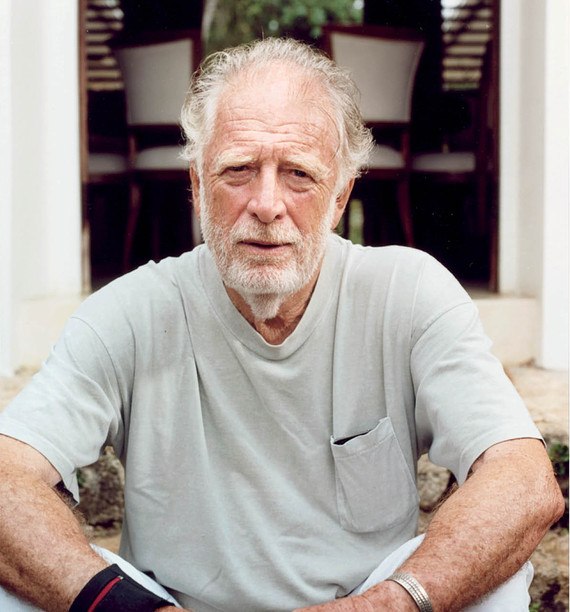

Blackwell has come straight from swimming in Goldeneye’s lush green lagoon, located mere steps from his front door. He’s dressed in a T-shirt and shorts, sporting espadrilles and bracelets around his wrists. Tall and stately, at 76, he looks like something of an aging hippie—one with a quiet English accent and a thirst for innovation.

Agricultural tourism was never on the agenda when he was growing up between Jamaica and London—teaching waterskiing in Montego Bay, selling air conditioners and studying accounting at Price Waterhouse. But neither was earning a berth in the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, an accolade the Island Records founder accepted in 2001. Born in London, Blackwell spent his early years on a large estate in Jamaica where his mother had grown up. He started his label in Jamaica in 1959 before returning to London, where he was educated, to sell records in the city’s West Indian communities. In the ’70s, Blackwell signed seminal reggae artists like Lee “Scratch” Perry, Burning Spear and The Wailers. Bob Marley’s subsequent stardom was a coup for Jamaica—not just Jamaican music—and cemented Island’s legacy. There were also albums from the B-52s, Tom Waits, Robert Palmer and U2.

Blackwell’s ease in the recording studio was a natural jumping-off point for his detour into hospitality. Two of his first properties—The Marlin Hotel, in South Beach, and Compass Point, in the Bahamas—included recording studios, making them natural hubs for rock stars and models. He had purchased Goldeneye—the former home of author Ian Fleming, who was a close confidante of Blackwell’s mother, Blanche Lindo—in 1976, but the accommodations at the time were modest. Fleming wrote his iconic James Bond novels in a monastic room with the shutters closed to the glorious view of his private beach.

Blackwell at his Goldeneye resort

Blackwell at his Goldeneye resort

By the mid-’90s, Blackwell owned a clutch of Art Deco boutique hotels in Miami and another on Harbour Island in the Bahamas, intimate places with bright colors, quirky designs and an atmosphere where celebrities felt at ease. Rather than rub elbows with the talent at industry functions, Blackwell created spaces for his artists and friends to visit him. “The people there!” says Barbara Hulanicki, founder of London’s legendary fashion store Biba, and the designer responsible for Goldeneye’s new interiors. “Beyoncé, the Spice Girls, Mick Jagger, you’d sit there saying to yourself, ‘I know that face,’ and realize you were sitting next to Prince.”

Blackwell calls this period “a magical time,” although his film company, Palm Pictures—another of his ’90s businesses—did not fare as well. “I think we’ve both come unstuck on occasion because we’ve followed our passions,” says fellow Englishman and record label founder Richard Branson.

But I don’t think either of us are really interested in business, per se. We love creating things.

Over the years, Blackwell added cottages to Goldeneye, inviting friends to visit. By the late ’80s he had opened it as a resort, but never widely promoted it. Again, he’d created a playhouse for the jet set—this time flying the Jamaican flag. “Miami was all rock ‘n’ roll,” says Hulanicki. “Whereas, you could tell that Goldeneye was such a personal thing for Chris.” No doubt in part due to the relationship between his mother and Fleming—the pair were close friends, part of a circle that also included Noël Coward and Errol Flynn. Blackwell had even worked as a location scout on the 1962 film adaptation of Fleming’s Dr. No.

THE LATEST BLACKWELL project began brewing in Jamaica nearly a decade ago. By 2004, he had sold his Miami portfolio of hotels (they’d been losing money) and narrowed his focus to Jamaica and the Bahamas. Each property had a cool celebrity mystique—regular guests included Kate Moss and Keith Richards—but their island locales and reggae soundtracks made them more approachable than stuffy. Blackwell insisted that the staff be front and center, encouraging them to forge connections with guests. Again, he hit on a winning formula by listening to the roots of Jamaican culture. “I’ve always looked for a location that is fantastic and then said, ‘Okay, how can we make it comfortable?’ ” Blackwell says.

I want people to enjoy the simplicity in the natural.

In late 2010, Blackwell expanded Goldeneye, adding new beach- and lagoon-front villas and amping up the marketing—with his personal touch still evident. The villa interiors have a simple, clean aesthetic and pops of vivid batik prints from the Royal Hut line created by his late wife, Mary Vinson, a Parsons-trained fashion and home furnishings designer, who died in 2004. (Grace Jones introduced them in the early ’80s.) The Logitech Squeezebox music system is loaded with an eclectic playlist curated by a DJ friend who lives in Tel Aviv. Red Stripes in the retro Smeg refrigerators are sold at a friendly $3 apiece. The villas have claw-foot tubs, outdoor showers and feature air-conditioning, despite Blackwell’s misgivings—he despises the way A/C cuts out “the sound of the sea, the crickets and the tree frogs. All those sounds which are so important to the sensory feel of Jamaica.”

Rooms at Goldeneye average $1,000 a night, but the vibe is warm and laid-back, encapsulating the languid rhythm of Jamaican life. “It’s where I recharge my batteries,” says fashion entrepreneur Emanuele Della Valle, who has been going to Goldeneye since meeting Blackwell through Naomi Campbell in the mid-’90s. He finds inspiration in its simple, casual days that contrast with the frenetic pace of New York. On previous trips to Jamaica, Della Valle had stayed in places where “guests were hostages of these huge hotels—you never get to know anything about the Jamaican culture.”

The idea of sharing his farm idyll—making it a more sustainable enterprise—grew slowly for Blackwell. (The only things Blackwell appears to do fast are walking, driving and his pet pastime: jet-skiing.) While the resorts had always relied on local providers for most of their produce, only importing what they could not source from Jamaica, Blackwell knew he had an impressive resource with his farm. Starting in 2006, Pantrepant made small periodic deliveries of lettuce, broccoli, cauliflower, cabbage, oranges and bok choy to Goldeneye. There was no official pipeline in place, but Blackwell was already contemplating how to scale operations in order to service all his resorts.

The allure of Pantrepant’s rolling pastures, its river, natural water hole and roaming wildlife is amplified by its isolation—it lies at the end of a beat-up, potholed road in the sleepy green parish of Trelawny. “It’s like setting back the clock 300 years,” says Della Valle.

The word organic finds its way into almost any description of Blackwell’s style. From a farming perspective, it was always the rule. The first thing Blackwell did when he bought Pantrepant was to eradicate the use of chemicals; he hated the smell and opted for a more costly, labor-intensive, natural method of farming. “What replaces the chemicals is people having to cut bush all the time,” he says. “But I like to create a few more jobs.”

I’ve always looked for a location that’s fantastic and said, ‘Okay, how can we make it comfortable?’ I want people to enjoy the simplicity in the natural.

—Chris Blackwell

Echoing his path in the music industry, his knack for unearthing talent would ultimately help him achieve his goals. His personal chef, Talcie Neil, worked for Blackwell and his mother for 30 years. Goldeneye’s executive chef, Nerissa Clarke, grew up near the resort and always dreamt of working for Blackwell. One of Blackwell’s two sons, Chris Blackwell, Jr. (his other son, Chance, is 12), now works on Blackwell Rum, another recent initiative that launched in the U.S. last year and is based on an old family recipe. (Blackwell’s grandfather purchased Jamaica’s leading rum company, J. Wray & Nephew, in 1917.)

Gardener Ramsey Dacosta has worked at Goldeneye since the days of “Commander” Fleming. Today, at 76, he still works part time, tending to Blackwell’s garden, carving coconuts for kids and planting fruit trees selected by guests. The grounds are dotted with plaques bearing bold-faced names who have taken part in the planting program. Their donations of $1,000 each go to Blackwell’s Oracabessa Foundation, named for a nearby town (home to many Goldeneye workers) to benefit local sustainable development projects.

The hire that positioned Pantrepant to become more sustainable occurred in 2011, when Gustavo Díaz came aboard as the farm’s general manager. As a graduate of Costa Rica’s Earth University, Díaz arrived with a wealth of knowledge about organic farming—and a five-year vision for what Pantrepant could become.

“I’m thrilled to have Gustavo because I know nothing about farming,” says Blackwell, who had heard of Earth University through a friend in Washington, D.C., and now provides funds for two Jamaican students to attend the school each year.

I know what I like—the produce and having lots of fruit trees that the birds like—but I never wanted it to look like a ‘farm farm’ with rows of plants. I want everything to look kind of natural. Which is, by any stretch of the imagination, an unprofessional approach.

The research, expertise and analytics come from Díaz, who talks at length about a slew of initiatives: the growth of weekly deliveries to Island Outpost resorts, now offering more than 30 different in-season fruits and vegetables; recycling the hotels’ plastics and glass—a concept so foreign in Jamaica that the broken-down pieces must be shipped offshore for processing; and collecting food scraps to feed to a colony of black soldier flies, which in turn produce larvae that are sun-dried and fed to chickens or livestock. “The whole idea is to close the loop,” says Díaz. “To cycle the nutrients back into the system.” He’s been collecting vegetable oil to eventually use as fuel for the farm’s diesel engine, and is planting trees to serve as “live fences” for the 700 acres of pastures.

To date, Pantrepant has diverted 20,000 pounds of recyclable materials from landfills; it has composted more than a thousand pounds of waste. The introduction of solar power has reduced the farm’s energy bills by 40 percent. Next up is the chicken project. “After seeing the movie Food, Inc.,” Blackwell tells me, “I thought, That’s it, I don’t want to eat any battery hens.” Soon, Pantrepant will supply free-range chickens to all three resorts’ restaurants and canteens. Pigs will follow.

Both farm manager and owner understand that their desire for Pantrepant to be fully sustainable is a long-term project. “The farm serves as the lungs of Island Outpost,” says Díaz. “A full integration of the farm and everything we do in hospitality is simply one of our core objectives.”

“It never ends,” adds Blackwell.

Given all of his efforts to promote Jamaica and its natural assets, I wonder why he hasn’t gotten into politics or worked for the tourism board—like his cousin John Pringle, the founder of famed Jamaican resort Round Hill, did in the ’60s. “I’m not suited for either of those things,” he says. “That requires thinking of what works best for the majority, and I like to walk my own path.”

He would, however, like to see more ardent promotion of Jamaican food among his tourism peers. Round Hill recently started their own farm-to-table dinner series, showcasing local purveyors, and the resort has its own vegetable and herb garden. A former Pantrepant farmer, Adam Miller, and his wife, Marika Kessler, have established their own CSA—Community Supported Agriculture—at nearby Potosi Farms. Other small-scale projects are peppered across the island.

“I would love to see a couple hundred places in Jamaica doing it,” says Blackwell. “I think Jamaica would thrive if we promote agriculture as a way to bring people here.” It would, he says, encourage guests to venture out of hotels and into local restaurants and food stalls.

I think it would help to foster the entrepreneurial spirit, which is so big in Jamaica, and give them a piece of the tourism business. That’s the most important thing that should happen here.

Corrections & Amplifications

Designer Mary Vinson died in 2004. The year was incorrectly given as 2009 in an earlier version of this article.

Source: online.wsj.com